The story of a king dividing his kingdom among his daughters was not an unfamiliar one for Shakespeare’s audiences. King Leir’s mythic tale had been told and retold in various styles for centuries. Twelfth century historian Geoffrey of Monmouth depicted the King’s story in his Historia Regum Brittanaie, or the History of Great Britain, circa 1135. This Leir would have reigned in the eighth century BC. Based off Monmouth’s Historia was Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland, second edition 1587.

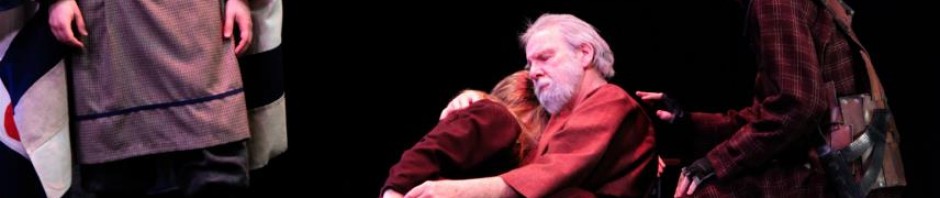

An illustration of King Leir and his daughters from a 13th century manuscript in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Shakespeare’s version follows the traditional anecdote closely in terms of the familial turbulence, but the youngest daughter’s characters, originally Cordeilla, succeeds her father after reclaiming the throne in the early texts. The elder sisters’ sons then overthrow Cordeilla, and it is not until she commits suicide and the last daughter is killed that peace is finally restored (Halio 20).

Edmund Spencer retells the story in his poem The Faerie Queene, printed in 1590, in which the youngest daughter, now called Cordelia, is hanged. His version begins:

Next him King Leir in happy peace long reigned,/ But had no issue male him to succeed,/ But three fair daughters, which were well uptrained/ In all that seemed fit for kingly seed;/ ‘Mongst whom his realm he equally decreed/ To have divided. Tho when feeble age/ Nigh to his utmost date he saw proceed,/ He called his daughters, and with speeches sage/ Inquired, which of them most did love her parentage.

Shakespeare most likely relied on another play, The True Chronicle of King Leir, which was first performed in the late sixteenth century and published in 1605. The ending in this earlier version mirrors the traditional story with Leir surviving and Cordella finally ruling England. This version varies from others significantly, however: the antagonistic sisters and husbands do not die but disappear from the kingdom; they overtly plot to murder the king; there is no Fool or Gloucester subplot; and Perillus (renamed Kent by Shakespeare) is never banished (Halio 21).

Shakespeare’s Gloucester plot was inspired by The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia by Sir Phillip Sydney, printed in 1590, which recounts a story of a father blinded by his treacherous bastard son then healed and succeeded by his legitimate heir.